< back to News list

Memories of Tragedy and Happiness

A Reunion in Romania

by Joseph Notovitz

As the son of a Holocaust survivor, I have heard countless stories about the suffering, cruelty and misery put upon the Jewish people during this sad time. But there is one story that has affected me most emotionally and profoundly. It is the story of my cousin Janka Festinger Speace (1916-1994), who after surviving concentration camps, documented a compelling, moving story of survival, redemption and the beginning of a new life.

Following the passing of Janka in 1994, one of her twin sons, Oscar, learned about a letter written by his mother after she was liberated by United States servicemen in 1945. From a small, modest apartment in Munich, to a new life in the United States, Janka wrote a 60-page, highly-descriptive, cogent letter to an uncle in Cleveland. Like a sharp-minded diary, she precisely recounted her day-to-day experiences in the camps. She wrote about her family, the friends she met, providing love and support to each other, the cruelty administered by the SS—Schutzstaffel (the “Protective” Squadron); remarkable details like the pitch blackness and screams where she was forced to sleep, the Gestapo removing her earrings with pliers, the rhythmic, torturous music the Germans played while Jewish prisoners were marched toward the camps, and her feverish search for a cup of milk to satisfy her dying sister Gizi’s last request.

The letter would be a treasure trove of information and understanding about the person their mother was—53 years after she wrote it. Oscar acquired the letter from Betty Silver, Janka’s sister in Canada. Written by hand, in Hungarian, it was soon translated, and her twin sons read it in profound concentration and silence. A new mission had emerged: This simply had to be shared with the world.

So as award-winning writers, Oscar set out to write a remarkable stage play, Janka, and David followed with the book, Janka Festinger’s Moments of Happiness—both works based on her correspondence.

Through an emotionally-charged performance by Actress Janice Noga as Janka (also Oscar's wife), the one-person play has been critically acclaimed and seen throughout the U.S., Covent Garden in London, Edinburgh Festival Fringe in Scotland and most recently, back to where Janka was born—Sighet, Romania.

In May 2012, I was fortunate to travel with my mother Clara to Sighet, Romania, a small northern town on the Tisa River, near the meeting of the Hungarian and Ukrainian borders. It was here, where Janka (my mother’s first cousin) spent her early childhood with her parents Kreindel and Chaim David, two sisters and two brothers, Betty, Gizi, Shlomo and Sandy. Our journey became an unforgettable family reunion and connection to the past. Joining Janka’s sons and granddaughter Ellen (from California and New Jersey) and cousins from Australia and Canada, we experienced a museum without walls; an exhibit that was not built by curators, but a participation; seeing and feeling the actual footsteps, aromas and ultimately the terror my cousins felt as children.

During our first day, we walked across the courtyard of our hotel to visit the home where Elie Wiesel was born. Now a museum guarded by a student, the house includes some original furniture, fireplaces and pictures. I took an authentic photo of the 1930s dining room, with what appeared to be a can of Arizona tea erroneously placed there. In the main living room there is a poster display presenting the changing Jewish Population from before, during and after the German occupation. Before the war, over 12,000 Jews in Sighet; after the war, a few dozen. It was at this precise location of two feet in width, where my mother felt a severe drop in temperature—as if something from the past was haunting her and this place.

We continued to Iuliu Maniu Street—and the homes of our cousins' parents and grandparents. Iuliu Maniu Street was a quiet, residential street designed for children to play and families to grow. The colors of structures reminded me of Key West—pastels of peach, pink and blue. Fences and surfaces were worn and rusted, as if the residents were just tenants. As we stood in front taking pictures, these residents came out and glared at us with discomfort and disdain. I could almost hear them asking, “who are these people standing by our property?” But I asked, who exactly are these residents, and how did they “acquire” that property?

We continued to Iuliu Maniu Street—and the homes of our cousins' parents and grandparents. Iuliu Maniu Street was a quiet, residential street designed for children to play and families to grow. The colors of structures reminded me of Key West—pastels of peach, pink and blue. Fences and surfaces were worn and rusted, as if the residents were just tenants. As we stood in front taking pictures, these residents came out and glared at us with discomfort and disdain. I could almost hear them asking, “who are these people standing by our property?” But I asked, who exactly are these residents, and how did they “acquire” that property?

During the spring of 1944, they came. While the children of Iuliu Maniu Street were playing against the beautiful backdrop of the Carpathian Mountains, they could hear and feel the rumble of the Nazi tanks. Within five days, all the streets in and out of Sighet were closed. My family and I stood in shock, imagining this happening only a few blocks from where we were standing. All stores were closed; much of their contents removed and taken by the “state”. Janka remembered all Jews having to give up everything they owned—jewelry, heirlooms, gold, cash and personal items they acquired during their lives. And then the disgraceful yellow stars started to appear.

During the horrifying days that followed, virtually every Jewish family in Sighet was rounded up and led to a synagogue-turned processing station. Those who could “not” prove they weren’t Jewish were sent to the Ghetto of Sighet—10,000 Jews squeezed into two small streets—with no food, medical care or access to the rest of the world. Janka remembered they lived there for the next six weeks.

During the horrifying days that followed, virtually every Jewish family in Sighet was rounded up and led to a synagogue-turned processing station. Those who could “not” prove they weren’t Jewish were sent to the Ghetto of Sighet—10,000 Jews squeezed into two small streets—with no food, medical care or access to the rest of the world. Janka remembered they lived there for the next six weeks.

At 4:00 am on a dark morning of May 15, Janka’s family was awakened by loud pounding at their front door. The Nazis gave them ten minutes to be outside with only a few pounds of belongings.

Then the painful walk to the train station. Thousands of families with bundles on their backs, crying children running in every direction trying to find lost parents; husbands and wives getting separated while being hit by canes and pistols from all sides.

Then the painful walk to the train station. Thousands of families with bundles on their backs, crying children running in every direction trying to find lost parents; husbands and wives getting separated while being hit by canes and pistols from all sides.

The Sighet train station was at the north end of Iuliu Maniu Street. That meant my cousins were forced to march past their homes and the street they once knew—a bizarre and ironic reminder of what they would never see again.

No historical museum can ever compare to standing in history. My cousins and I took this path north a few blocks to the train station. There, no cattle cars were waiting to take us to Poland and Auschwitz, only a 1950s passenger train to Bulgaria. But the station floor remained unchanged – its broken tiles had not been replaced since 1933. The ceiling and light—unchanged since my family last walked under them. Only the decay of age covered all the surfaces. From the station waiting area by the tracks, I could see the watchtower, where German soldiers guarded with MG-42 Maschinengewehr sub-machine guns, as families were loaded onto cars—almost 100 men, women and children of all ages mercilessly squeezed into each sealed, hot, airless cavern.

No historical museum can ever compare to standing in history. My cousins and I took this path north a few blocks to the train station. There, no cattle cars were waiting to take us to Poland and Auschwitz, only a 1950s passenger train to Bulgaria. But the station floor remained unchanged – its broken tiles had not been replaced since 1933. The ceiling and light—unchanged since my family last walked under them. Only the decay of age covered all the surfaces. From the station waiting area by the tracks, I could see the watchtower, where German soldiers guarded with MG-42 Maschinengewehr sub-machine guns, as families were loaded onto cars—almost 100 men, women and children of all ages mercilessly squeezed into each sealed, hot, airless cavern.

But I was not completely satisfied with this museum, as something was missing. At first glance, there appeared to be no sign of any locomotives or cattle cars from the 1940s. I proceeded to delve more profoundly. I crossed the two active tracks and walked west along the northern-most track, past a large steel barn and a grizzly train worker. Then I saw it. German steam locomotive number 1501062. It was built in 1943 and towed “military cargo” during the war. Continuing a few more steps west, I saw a cattle car from the same period. These trains weren’t on display in a museum exhibit—they were simply “left” here by the people who operated them. Now I felt the severe drop in temperature.

But I was not completely satisfied with this museum, as something was missing. At first glance, there appeared to be no sign of any locomotives or cattle cars from the 1940s. I proceeded to delve more profoundly. I crossed the two active tracks and walked west along the northern-most track, past a large steel barn and a grizzly train worker. Then I saw it. German steam locomotive number 1501062. It was built in 1943 and towed “military cargo” during the war. Continuing a few more steps west, I saw a cattle car from the same period. These trains weren’t on display in a museum exhibit—they were simply “left” here by the people who operated them. Now I felt the severe drop in temperature.

The Old Jewish Cemetery (Cimitirul Evreiesc) was our next stop. While waiting for a guide to unlatch the rusted, barb-wired gates, my cousin Greta asked a local historian, “Are there other Jewish cemeteries here?” My mother quickly replied, “Why, you want more?”

The Old Jewish Cemetery (Cimitirul Evreiesc) was our next stop. While waiting for a guide to unlatch the rusted, barb-wired gates, my cousin Greta asked a local historian, “Are there other Jewish cemeteries here?” My mother quickly replied, “Why, you want more?”

Once inside, the first headstone I found was Kreindel Festinger, mother of Janka (who my mother was named after), and grandmother of my cousin David Festinger. It strangely appeared as if it were just installed—clean and completely intact. Upon seeing this overwhelming link to their past, David and his wife Tracy fell to their knees and cried. Then, the second discovery. While he was in his 80s and visiting us, my cousin Lajos gave my mother a picture from this cemetery, taken in 1924. He labeled it “Grandfather Shlomo ben Shmuel.”

Using the picture as a guide, and orienting myself to face a nearby roof that was in the picture (still there today), I searched through hundreds of gravestones until I found a stone to the right of Shlomo’s depicted in the picture. Now black and deteriorated from 88 years of wind, rain and sun, it had become grossly tilted and covered with mildew, yet I could read the letters “Rafuel” in Hebrew. And at its left was only the grave of Shlomo, not the towering headstone that was once there.

Using the picture as a guide, and orienting myself to face a nearby roof that was in the picture (still there today), I searched through hundreds of gravestones until I found a stone to the right of Shlomo’s depicted in the picture. Now black and deteriorated from 88 years of wind, rain and sun, it had become grossly tilted and covered with mildew, yet I could read the letters “Rafuel” in Hebrew. And at its left was only the grave of Shlomo, not the towering headstone that was once there.

Our trip culminated with the premier performance of Janka at the George Enescu Theater. Maia Morganstern, an acclaimed Romanian actress, seemingly became possessed by the spirit of Janka Festinger. She unfurled her story to an audience as if they were guests in her living room. Instantly changing her emotions from sadness, to happiness, to anger, fear then laughter, I looked back at the seats behind me and saw more than eighty percent of women and men in tears.

This trip has changed my life, and has brought me closer to my family than I ever have been. I did not merely peer into their lives 68 years ago; I felt I was there with them—through their joys and suffering.

This trip has changed my life, and has brought me closer to my family than I ever have been. I did not merely peer into their lives 68 years ago; I felt I was there with them—through their joys and suffering.

Are we Jews happy throughout our lives for even one minute or is there for us even a minute of perfect happiness?

- Janka Festinger

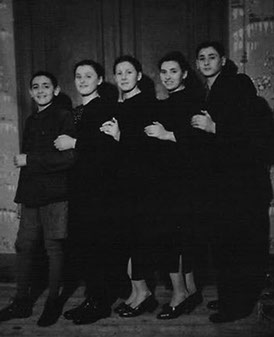

The five Festinger children, (l to r) Shlomo, Betty, Janka, Gizi and Sandy, 1937 in Sighet, Romania.

Iuliu Street, taken from in front of the Festinger house, facing south toward the train station.

Ron Silver, David Speace, Oscar Speace and David Festinger, in front of the original Festinger home on Iuliu Maniu Street. This is where their parents and grandparents Lived. The train station at the end of the block is where the Germans led them.

Sighet-Marmatiei train station

The Sighet-Marmatiei train station tower. In the Spring of 1944, the Nazis vacated virtually every Jew from Sighet. But first hey were forced to walk past their homes, with the Carpatian Mountains and their lives behind them.

The cattle car is similar to the one photographed in 1944 with Jews inside it (in the photo archives of Yad Vashem).

The cattle car is similar to the one photographed in 1944 with Jews inside it (in the photo archives of Yad Vashem).

The wall and main gate of the old Jewish cemetery.

Above: Shlomo Festinger's grave - the way it looked in 1924, and 2012 (below).

The George Enescu Theater, site of the Romanian premier of Janka Festinger's Moments of Happiness.

Maia Morgenstern, star of Janka Festinger's Moments of Happiness, giving autographs following her debut performance in Sighet, Romania. Maia, a well-known actress in Romania, was cast as Mary in Mel Gibson's Passion.